B.C.’s Lagging Job Creation Indicates a Weakening Economy

British Columbia is experiencing a divergence between its working-age population (aged 15 years and older) and job creation. The number of people entering the workforce continues to rise, but employment creation has not kept pace. The result is rising unemployment.

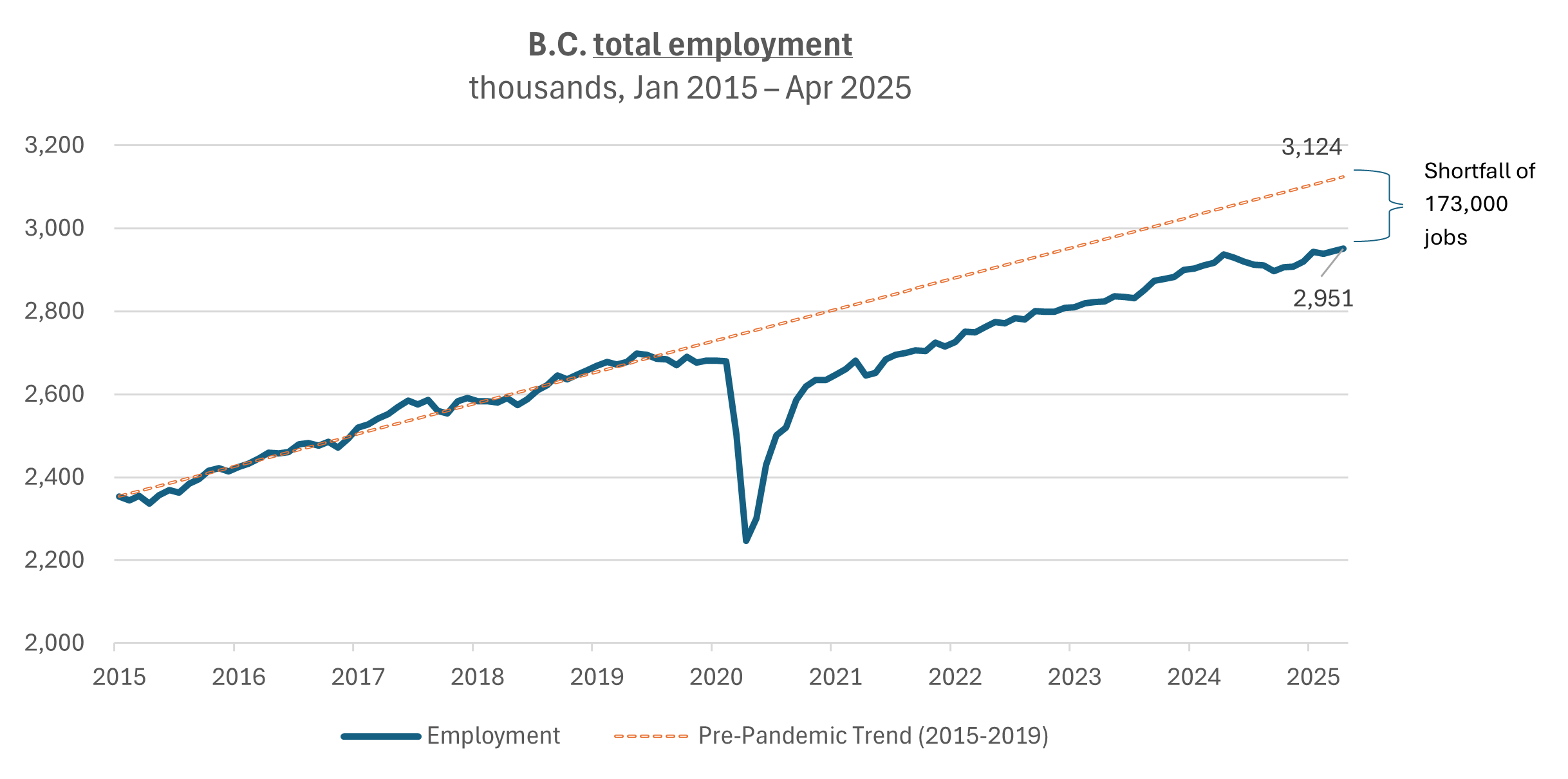

Had total job growth continued along its pre-pandemic trajectory (2015–2019), B.C. would have approximately 3.12 million employed workers today. Instead, as of April 2025, the province’s employment sits at 2.95 million, which is roughly 173,000 jobs below that trend (Figure 1).

Meanwhile, due to federal immigration policies, B.C.’s working-age population growth has significantly outpaced its pre-pandemic trend. Based on that trajectory, B.C. would have had around 4.66 million working-age residents today. Instead, the actual figure is 4.83 million. This is 169,000 people higher than the pre-pandemic trend (Figure 2).

In other words, relative to pre-pandemic trends, B.C. has added many more potential workers than it has created jobs for.

Figure 1: B.C. employment growth has stalled relative to

pre-pandemic trend

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 14-10-0287-01 Labour force characteristics, monthly, seasonally adjusted.

Figure 2: B.C. working-age population growth has accelerated beyond pre-pandemic trend

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 14-10-0287-01 Labour force characteristics, monthly, seasonally adjusted.

The imbalance between employment and population growth has become even more pronounced over the past 12 months. Between April 2024 and April 2025, B.C.’s working-age population increased by 130,000 people (+2.8%), while employment rose by just 14,000 (+0.5%) —the third weakest performance among Canadian provinces. This is also the second widest gap between population and job growth in the country (Figure 3). The data suggest B.C.’s labour market has struggled to absorb the influx of working age people.

Figure 3: Between April 2024 and April 2025, B.C. recorded the second largest gap between population growth and job creation of any province

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 14-10-0287-01 Labour force characteristics, monthly, seasonally adjusted.

Over a longer time horizon, the slowdown in employment growth becomes even clearer. Between 1976 and 2024, employment in B.C. grew at a compound annual growth rate of 2.1%. But if we zoom in over the past five years, that pace has slowed to just 1.7% per annum (Figure 4). In contrast, every other province except B.C. and Alberta has matched or exceeded their historical employment growth rate over the last five years.

Figure 4: B.C. is one of only two provinces where recent job growth trails long-term performance

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 14-10-0027-01 Employment by class of worker, annual (x 1,000).

This pressure is now showing up in the unemployment rate. B.C.’s jobless rate has increased from 5.0% to 6.2% over the past year — the sharpest increase among provinces (Figure 5). Historically, a rise of more than one percentage point in the unemployment rate over a 12-month period has only occurred during recessionary periods like the early 1980s, the early 1990s, the 2008-09 global financial crisis, and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 6).

Figure 5: Between April 2024 and April 2025, B.C. had the steepest increase in the unemployment rate of any province

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 14-10-0287-01 Labour force characteristics, monthly, seasonally adjusted.

Figure 6: B.C.’s recent rise in unemployment is unmatched outside recessionary periods

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 14-10-0287-01 Labour force characteristics, monthly, seasonally adjusted.

*Shaded areas represent national recessions or economic slowdowns in Canada, including: the early 1980s (1981–1982), early 1990s (1990–1992), the global financial crisis (2008–2009), and the COVID-19 recession (2020). The 2001 slowdown is included due to its labour market impact, despite no formal recession in Canada. Historical recession periods based on: C.D. Howe Institute, Business Cycle Council Historical Recession Dates (2021).

Conclusion

B.C.’s working age population has been growing faster than new job creation. Employment growth is underperforming its pre-pandemic trend. The unemployment rate has risen quickly over the past year and in a way rarely seen outside of recessions. Taken together, the data suggests a weakening economy.